(This article is a translation of the Burmese language version that ISP-Myanmar posted on its Facebook page on April 12, 2021.)

Since Myanmar’s military seized power in February, the photos and videos of its crackdown on protestors include images of dead children, protestors shot in the head, and violent abductions by state security forces. The atrocities committed by state security forces against the population have created widespread resentment towards the military-led government and, at the same time, raised questions for scholars about the circumstances leading to such brutality. Scholars have not yet reached a consensus about the causes of coup d’états and how coup-makers consolidate power. One approach is to look at the role of political culture in Myanmar, emphasizing perceptions of state power from the earlier reign of monarchs.

∎ Key findings in brief

Toe Hla, a renowned Myanmar historian, explains that htee-nan, a Burmese term for the reign of a king or a throne, is seen as min-see-zein or deeply entrenched privilege in Myanmar’s history. He claims that this perception is the main reason for despotic rule by monarchs in Myanmar, suggesting that since Myanmar kings view the throne as a privilege, the governing system in Myanmar has become chaotic (Toe Hla, 2019). The kings did not perceive the power to rule as involving a duty to serve the people. Instead, monarchs considered their wives (or queens), concubines, and palace servants along with taxes and other tribute from subordinate kingdoms as the fruits of their privileged position. As these were the king’s property, he could use them as he wished. Toe Hla claims that monarchs abused state power because of their belief that they owned the land and water (ibid.). The kings viewed power as a privilege that was appropriated, private, and had nothing to do with others, as it belonged to them because they obtained it. David I. Steinberg (2001) argues that according to conceptions of Myanmar political culture, people do not think of state power as an infinite entity that can be divided, shared, expanded, or attained by negotiation but, instead, as a finite entity that can only be gained through winner-takes-all contests. Maung Maung Gyi (1983), a respected Myanmar historian, points out that Myanmar people have an “all or nothing” mindset in general. Citing Myanmar proverbs that “the defeated will be buried, the victor will be crowned” and “eat only meals of delight or die starving”, Maung Maung Gyi claims that according to Myanmar political culture, there can only be a victor or a defeated. In short, scholars have argued that traditional political culture in Myanmar follows a logic that “if you don’t kill your enemies, you will be killed by your enemies.”

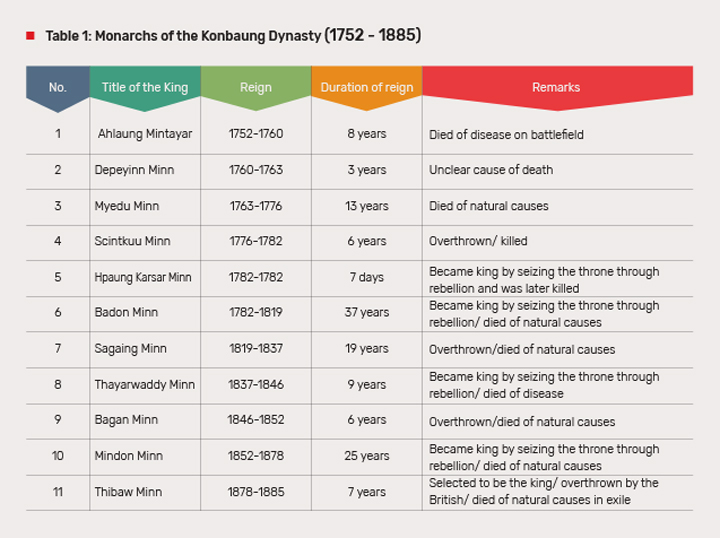

Source: Toe Hla (2019)

As shown in Table 1, Toe Hla (2019) finds that among the 11 kings of Myanmar’s Konboung Dynasty (1752 – 1885), at least four of them seized the throne from an incumbent king by force. He notes that people should not assume that kings capture the throne because they want to save people from the atrocities of unjust kings. Nor did they risk their lives and take the throne because of any sense of duty to bring about peace and prosperity for the benefit of the people (ibid.). Instead, they seized the throne because they wanted to enjoy the privileges of monarchy together with their numerous wives and their greed for power, which they viewed as a tool enabling them to do whatever they want.

In sum, power is conceptualized as a privilege and, thus, one must conquer the throne and take power. When taking over the throne, there must not be any compromise. The monarch’s actions align with notions of political culture expressed in Burmese proverbs emphasizing a “winner take all” mentality, in which the defeated are buried while the victorious take the throne. These beliefs and practices are in line with what several scholars regard as fundamental features of Myanmar’s political culture expressed in people’s views of state power, abuses of power, and power competition throughout Myanmar’s history. However, instead of submitting to the unjust and brutal political tradition by following and supporting evil kings, Myanmar history also has instances when people have challenged this tradition. These examples can provide opportunities for reflection and learning how to correct bad practices.

∎ Why does it matter?

In the current anti-coup, mass revolutionary movement, there are efforts by people not only to uproot the existing legal, administrative, and economic systems but also the elements of political culture that encourage despotic rule. Moreover, the protesters are revolting against the administrative system and the norms and values of society. One of the major contributions of the anti-coup mass movement is that it has fundamentally changed the people’s perception of state power and the ruling class (See “The determinants of success and failure of a social movement,” What Matters No. 9). Only when people break free of a “blood-stained” political culture that replaces one dictator with another can a political system that governs and supports society take root. Moreover, it is necessary to establish a democratic political culture so that the people no longer suffer the consequences of coups when those in “the palace” or in power disagree over power-sharing arrangements. A more democratic political culture perceives power as a duty derived from the people rather than a privilege. Citizens must be able to control those in power through checks and balances. Being assigned a position of power means that serving the people is mandatory. Thus, it is important to study how Myanmar people understand “power” from the perspective of Myanmar’s traditional political culture.

∎ Is it relevant to Myanmar?

Throughout Myanmar’s political history, deposing kings through a palace coup often involved killing a king, who was often a relative of the power seeker. In one particularly bloody instance, over forty princes were massacred so that a prince could ascend to become one of the last kings of the Konbaung dynasty. Almost every Myanmar dynasty faced succession problems. While some were successful in managing them, others were not. From the monarchical period to the present, the transfer of power from one king or leader to another has not been smooth and often resulted in bloodshed.

The current junta claims that its coup on February 1st was not a total coup but instead a temporary declaration of a state of emergency. The coup leaders have tried to portray the coup as reflective of the politics in Nay Pyi Taw, in which the Tatmadaw seized state power because of vote-rigging by the National League for Democracy in the November 2020 elections. Given the absence of evidence, their claims have fallen on deaf ears. As the people’s revolution drags on, the anti-coup movement leaders and street protesters claim that they are not supporting a political party or an individual leader. The protesters have made it clear that they are rejecting the military’s unjust seizure of state power and its use of violence to address conflicts over the transfer of power from one government to another. Moreover, the protesters clearly do not accept efforts by the military to resurrect a dictatorship.

Myanmar’s military leaders staged the coup because they see wielding state power as tantamount to having privileges and riches. They fear that their ill-gotten private wealth might be seized without the protection of their power to rule and control, and they are afraid of losing out on new opportunities for acquiring wealth through corruption. Therefore, in the aftermath of the coup, foreign governments have either imposed or considered initiating targeted sanctions, while local boycotts initiatives of businesses linked to the coup plotters have emerged.

Based on a view that holding state power provides a privilege to rule and riches along with the belief that “the defeated will be buried, the victor will be crowned,” Myanmar’s military authorities are using extreme violence in an effort to put down anti-coup protests. As a consequence, not only the Myanmar people but also many others have seen images of shocking events in urban areas not witnessed in decades. Therefore, studying Myanmar rulers’ view of state power together with the push back against norms and values can contribute to a transformation of Myanmar’s political culture. The historical research on the monarchy and traditional political views about power in Myanmar are particularly relevant to the current situation. When people change their perception of power from one limited to kings or other rulers so that it expands to encompass public affairs and the return of power back to the people, people can check and balance the tradition of the despotic monarchy with a democratic system. Only then can totalitarianism be eradicated, and pluralism can flourish.

∎ Further Readings

Maung Maung Gyi. (1983). Burmese Political Values. The Socio-Political Roots of Authoritarianism. New York: Praeger.

Steinberg, David I. (2001). Burma: The State of Myanmar. Washington, D.C. Georgetown University Press

Toe Hla. (2019). ရာဇဝင်ထဲက မင်းဆိုးမင်းညစ်များ [Bad Kings in History]. (No publication information).

◉ What Matters ISP-Myanmar covers a section entitled “What Matters” that could benefit the current anti-coup mass movements through a series of research work. This section aims to introduce issues and data that should be addressed in a short, easy-to-read manner and accessible to everyone based on research findings. The introduced facts, cases, and data are intended to be a thought-provoking stimulus, but not as a definite view. The purpose is to make the data presented more accurate and complete. In this series, ISP would try to answer three questions in general: 1) what is the issue of concern? 2) why does it matter? 3) is it relevant for Myanmar? Addressing these questions does not involve an exhaustive examination but covers the relevant elements and claims. Thus, each issue of “What Matters” provides a list of suggested readings and references for further study. In the current situation, this section will focus on research findings related to three research topics. These are: 1) research findings related to coup d’état 2) research findings on mass movements 3) research findings on how the international community (especially powerful foreign countries that can provide significant support ) intervened in military coups and the authoritarian states. The research will be based on comparative studies. Research data collected by local partner organizations will also be requested and respectfully presented in various forms from time to time.